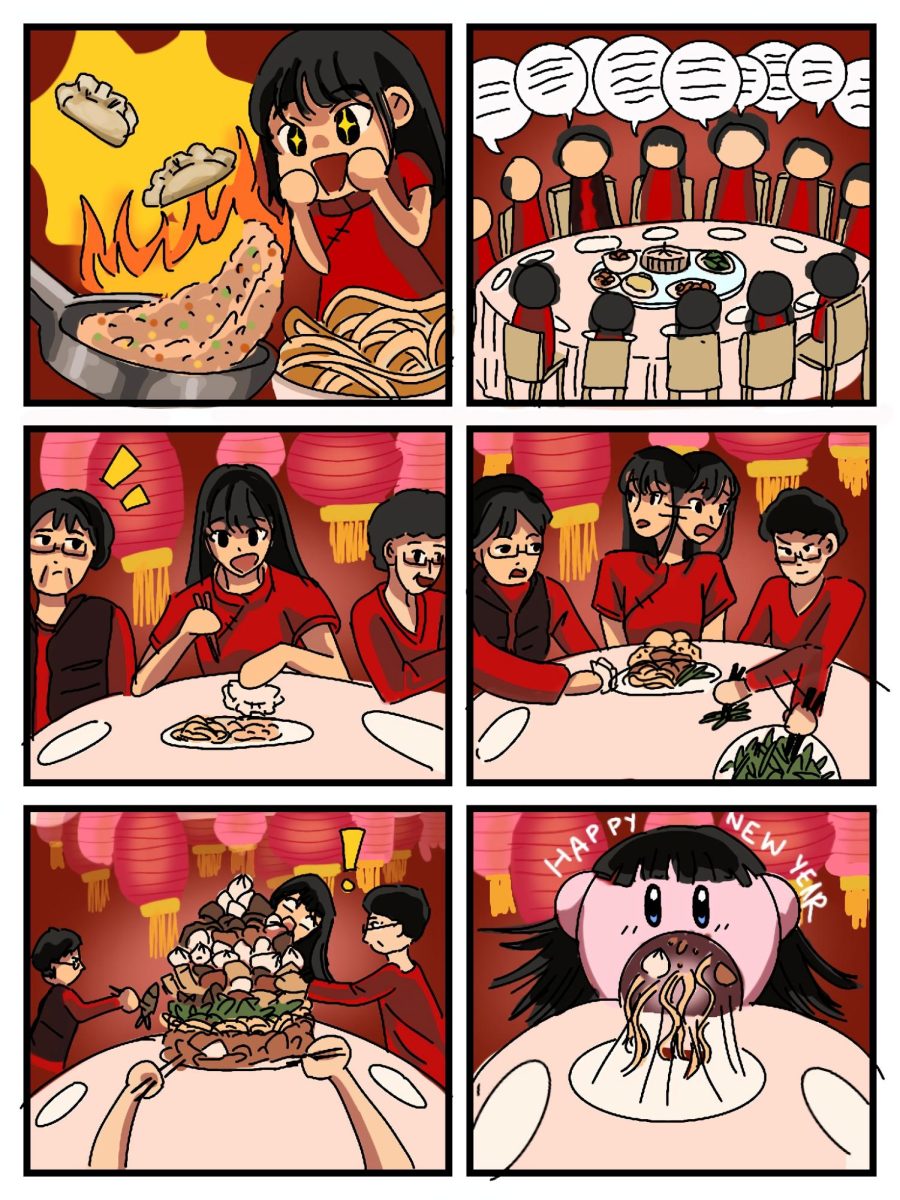

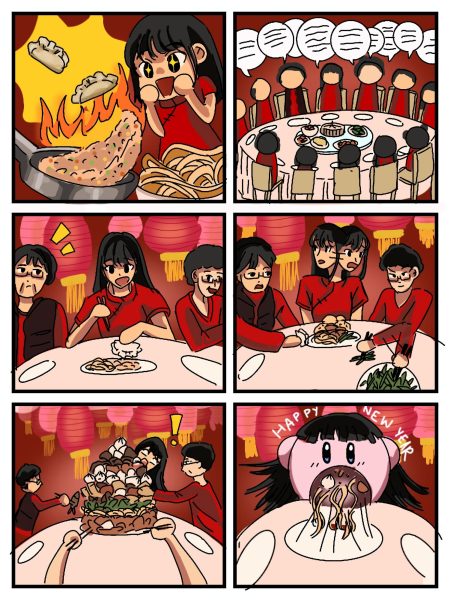

Comic by Paige Hoang

Lunar New Year: the celebration rooted from East and South East Asia that celebrates the entrance for the upcoming year with prosperity; highlighted for its bright red and gold colors in China and Vietnam, for the colorful hanboks and dances in Korea, or for the release of fireworks that illuminate the sky throughout parts of Asia. But as an American, participating in the traditions of Asia always looked different. My experiences with Lunar New Year have always centered around the dinner table. Memories of dim sum restaurant visits, visits to my grandparents house, or attending fancy restaurants that are only called for by this holiday signified Lunar New Year for me. These moments reminded me of my Asian roots among the American traditions I’ve assimilated with and as the saying goes, “food is a universal language.” This statement holds relevance especially for me since being a second generation has resulted in an identity conflict between English vs. Cantonese/Vietnamese. It only reminds me of my own conformity to a broader American culture instead of the individual cultures of myself. But this language barrier can only be so prominent in the midst of a good meal.

In the case of Lunar New Year, or other holidays that call for a family reunion, food becomes the language we all understand. Thus the coming together with my Chinese side of my family marked the beginning of my New Year for 2025. The start of the meal is always an overwhelming one, but a start I look forward to. With the abundance of food and the knowledge of the limited stomach space one has, it becomes a challenge my siblings and I compete with. The more common foods, such as fried rice or crispy Cantonese chow mein, test our speed as the dish is always emptied first. But other dishes such as mixed vegetables, tofu, or meat were a challenge of tolerance. I can never forget the guilt after each meal when those dishes were left to be stored away in a fridge rather than our stomachs.

The food itself is not the only way connection with my family and culture occurs, it’s also in the mannerisms and culture of food sharing. A meal with Asian “Aunties” is never without their passive comments that suggest to eat less or more, especially in the form of commenting on your plate or making suggestions based on the health of the food. I strongly recall the instance my sister and I had experienced this phenomenon. We were at an event related to an organization that reaches to rural communities in Vietnam and our exposure to Asian Aunties increased tenfold. Every new dish that came out of that restaurant kitchen, the aunties radar turned on. They were quick to pinpoint our empty plates and fill it with every dish. Reluctantly eating fried fish or shark fin soup became cemented in my memory. Piles of honey walnut shrimp mixed with loose grains of rice and green beans were encased in the sauce of pork and chicken. And in the case of my sister and I’s hesitancy to eat certain food is when the aunties felt the most compelled. Fish was never something my taste buds could enjoy and nor for my sister. But the unspoken submissiveness of the asian nieces and nephews was something we have become accustomed to. Piles of fried fish eventually appeared on our plates and I reluctantly ate both our plates. The auntie’s comments slipped in as I managed to take bites; “fish will help for your bad eyesight,” she said while pointing to my sister’s glasses, “It improves your eyesight.”

Chopsticks move quickly in these settings. But the food piling doesn’t end, not until dessert arrives. Expecting cake, brownies, ice cream, or cookies at an Asian restaurant will only lead to disappointment. The food brought out wasn’t a familiar sago dish, cut fruit, or che thai, dishes my family often eats, but an unfamiliar gummy blob. Even in writing my experiences, I fail to understand what the Vietnamese dessert was. As my aunties happily ate their spoonfuls of taro glob mixed with stray ingredients like mung bean, a bowl filled with the goop reached me. To say I didn’t enjoy it was an understatement, but that comes with the price of being far from my cultural roots and accustomed to eating the processed foods of America.

Although many other Asian Americans can relate to a similar distance to their culture itself, the language of food never fails to find a relatability that connects me to my culture. Food has been one of the strongest connections I have with my Asian roots and with the recent Lunar New Year that occurred in late January, it compelled me to illustrate a comic regarding this relatable experience that can resonate with other Asian Americans, and for the sake of a simple recognition for myself to remember my Asian counterparts.